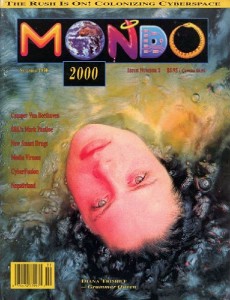

Mutant Glory: The MONDO Moment (MONDO 2000 History Project Entry #33)

While I mostly employ a playful, self-deprecating voice throughout the upcoming epic combined memoir and as-told-to history of MONDO 2000, I’ve been advised that — somewhere toward the beginning of the book — I should let people know just how brightly the MONDO star shined . Here then is a segment from the chapter, “Mutant Glory: The MONDO Moment” from the upcoming book, Use Your Hallucinations: MONDO 2000 in Late 20th Century Cyberculture. Some particularly strong parts are under embargo until publication, for a variety of reasons, so if it seems a bit discontinuous, that’s why. Â

Still, pardon my ego, or use it as if it were your own.

I’m seated on the couch in the living room of the MONDO House, the neogothic aerie high (in every sense) in the Berkeley, California hills; my blue fedora with the Andy Warhol button rakishly titled to the right, a hint of my beyond-shoulder length hair swept across my right eye, femme fatale style. It’s the same couch where, earlier this afternoon, Queen Mu had refused the Washington Post photographer’s suggestion that she and I pose John and Yoko style… naked… for the Post Arts & Leisure secton cover story about MONDO 2000. Â

The editorial meeting was running longer than usual. Mu had held the floor for almost an hour with a monologue that veered from her recent argument with Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek about Jim Morrison’s use of Tarantula Venom as an intoxicant — Morrison, in accordance with Mu’s gonzo anthropological researches, had joined a centuries-old secret brotherhood of poets and musicians in the use of this dangerous substance for Orphic inspirations; to the unending details of said tarantula venom theory; to the connections that simply must exist between our Mormon printers in Nevada and John Perry Barlow and the CIA and how they were all plotting to destroy us with a new magazine called Wired; and finally to the efficacy of writing after taking a few tokes of marijuana and then putting on Animals by Pink Floyd (to which our unofficial GenX spokesperson Andrew Hultkrans muttered, “Pink Floyd? It must be a generational thing.â€). When Mu was on one of her strange fantastic rambles she somehow didn’t seem to need to stop to breathe, so there was never an opportune moment to interrupt. Finally, she decided she was thirsty and went into the kitchen to boil some tea.

The editorial pow wow had produced the usual stuff — good stuff, as a matter of fact. An interview with early singularitarian Hans Moravec was in the works. Some peculiar and obscure German industrial band/performance art group had contacted us looking for PR and this might pair up nicely with the Laibach interview that Mark Dippe and Kenneth Laddish had submitted. Mad Lester Thompson had finally turned in a pretty good “Ultratech†column, rounding up of the latest in homebrew Virtual Reality and cheap digital video tech. St. Jude told us her “Irresponsible Journalism†column titled “The Grace Jones School For Girls†was almost ready and asked if her interview with Mike Saenz about his porn CD ROM, Virtual Valerie, had been transcribed yet. Our Art Director, Bart Nagel, as usual, said something that made everybody laugh.

Presently, Queen Mu returns to the living room with her cup of tea and our quiet, softspoken music editor Jas. Morgan pipes up. “Liz Rosenberg says Madonna will review the new Papal Encyclical for us,†he understates. My famewhore eyes nearly pop out of my head. “Be sure to follow up on that,†I say. Everyone else feigns blasé.

This was the age — the heyday — of MONDO 2000. A shorter but far stranger trip, if you catch my drift.

You didn’t hear about it? Well then, indulge me as I let some other voices tell you that I’m not hallucinating; not this time, anyway. There was, in fact, a MONDO moment and it seemed somehow important to some interesting people.

There will be plenty of time for self-deprecations, stinging criticisms and embarrassing revelations later, when we return this epic true adventure story back to its beginnings and follow it through ‘til its mad finale. But for this chapter, let’s bask in MONDO Mutant Glory.

Diana Trimble: You know how certain people, places or things can come to define an era? The same way that clubbers d’un certain age speak wistfully of the “MK years†in New York City or “the Hacienda era†in Manchester; the same way you can’t talk about the art scene of the 1960s without talking about Warhol’s Factory? Well, that’s the way certain people who were in the Bay Area during the “MONDO days†feel about the house up on the mountain where madness met inspiration for a few remarkable years that directly influenced the development of popular culture on a global scale; a little-recognized fact for which proper credit to MONDO 2000 is long overdue.

It’s one of the best-kept secrets of postmodern history: the Bay Area psychedelic revival and the explosion of computer science innovations of the late 1980s and early 90s were not only simultaneous and connected by geography but involved deeply interconnected personnel.

Rex Bruce: The MONDO scene was like the escape hatch out of the 80’s. While hanging onto the rebellious aspects of punk, it successfully retrieved some of the more colorful aspects of the sixties — the hippyish candy raver thing — along with a very thoughtful mingling of technology which had just gone exponential.Â

It was the beginning of the period we are still in, pretty much. Nobody really knew what the web was back then or what enormous potential it held. People in the MONDO scene knew and were going at it full force.Â

Emergent technology is still a huge area of cultural change. The cyberpunk people made it a movement and an identity — the scene grew to be a substantial part of a long history of bohemian culture that runs against the grain. This time it was armed with the internet, smart drugs, ubiquitous technology and the ubiquitous interface we still love and live in daily. It both began and predicted the times we live in.Â

Douglas Rushkoff: The idea of having a scene… a place… I mean, oddly enough, MONDO was the last scene of the last era. It’s the last sort of Algonquin group or whatever. I mean, physical reality isn’t what it used to be. Now you create a Facebook group to do what MONDO did.Â

A physical scene… it’s so much more fertile. What I experienced more than anything else in that whole cultural milieu was: “Here are human bodies and human egos attempting to navigate this wholly discontinuous hypertext reality; trying to live in — and with a full awareness of — these liminal transition states.†And now, when we’re fully in the Internet era, it’s totally easy to do if you leave the body fucking behind. It’s totally easy to do if your friends are on Facebook and you’re just jerking off to their pictures or something. But try doing that for real. It’s that physical and psychic stress that someone like R.U. Sirius or Stara or Jody Radzik put themselves through… that’s when you gotta start worrying about things like gender and psychogenic dystonia [LAUGHTER]… just the basic… hold your fucking self together, man! [LAUGHTER] You don’t have casualties of the same sort in the Facebook era. It’s a different thing. It’s bloodless. There’s no pubic hair in that reality. (Laughter).

Randy Stickrod: You had the feeling that the people who were creating this were tapped into some source that was outside of the range of the rest of us ordinary mortals. I’m serious, man! It was the real thing… the real fountainhead.Â

William Gibson: MONDO was arguably the representative underground magazine of its pre-Web day. It was completely outside what commercial magazines were assumed to be about, but there it was, beside the commercial magazines. I was glad it was there. And then, winding up on the cover of Time — what does that do? How alternative is something that makes the cover of Time? Could MONDO even happen today?Â

Â

Robert Phoenix: Around 1992 or ’93, MONDO was so on fire. They’d been on the cover of Time and had a major feature in Newsweek. Heide Foley was the poster child for the cybergrrl. She was it! Everybody was sniffing around MONDO. MTV was at MONDO. Apple Computers basically wanted to advertise in MONDO for life! It was a really, really, really big moment. I’ll never forget walking around the floor of Macworld with copies of MONDO to hand out. It was like I was passing out the Holy Communion. It was like, “oh my God, oh… MONDO! Thank you!â€

Â

Josh Ellis: When I interviewed Neil Gaiman, he said something to me I’ve never forgotten: “MONDO 2000 was the coolest thing in the world for six months.” And it’s true, although I do think it was a little longer than that.

Â

Hakim Bey: I can’t help thinking that the world, not just MONDO 2000, came to an end in around 1997. And we didn’t know it. And we’re living in the ruins.