The Impatience (And Genius) Of Jobs: An Interview with Walter Isaacson

I never felt a particularly intense curiosity about the life and personality of Steve Jobs until the night he died. Oh sure, he was a sort of hip entrepreneur from the baby boom, so there was always a glimmer of interest — somewhat along the same lines as the vague interest I would have in the life of Richard Branson. But my tastes in favorite biographies would tend to the more extravagant; a Timothy Leary or a Keith Richards or an Antonin Artaud or a Salvador Dali (and I must confess to a taste for the occasional bio of a power mad dictator).  Entrepreneurs, however extravagant or autocratic in their realm, would come up short in terms of satisfying whatever perverse delights in abused privilege, eccentricity, cosmic ambition and/or mighty flame-out I might hope to find in my favorite biographies.

But on the night Jobs passed, I took a look around my home and realized that my world is intimately suffused with the ghost of Jobs’s creativity — all those beautifully designed complex and total-package mechanisms for communication and creation are deeply woven into the proverbial fabric of my life. Plus, he was one of those successful acidheads whose embrace psychedelic veterans like myself like to wave as a banner against the clichéd assumptions the mainstream has about those who have dipped their psyches in that font of lucid vision and/or sensory overload (depending).

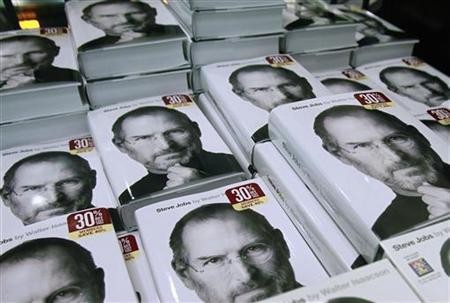

I immediately contacted Walter Isaacson to find out if I could get a copy of his then-upcoming official Steve Jobs biography for Acceler8or and interview him about it.

The bio did not disappoint. While no one reading Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson would come away comparing Jobs’s excesses and temperament to, say, an original dadaist or a major 1960s rock god, by most lights, he had personality and artistic sensibility to spare — and his visionary sense of self and determined refusal to do anything any other way than his own — makes for a lively and compelling read.

Isaacson lets his own prose sparkle as never before — including a use of playful titles and subtitles. It’s fun.

I conversed with Walter Isaacson via email.

RU SIRIUS: At the halfway mark in reading the book, my most prominent thought is…. nobody could emulate this guy – his behaviors or even his business strategies and methods — and expect to succeed in business.  More likely, someone else would get punched in the head fairly frequently.  So I guess to formulate this as a question: what do you think about this observation…  and… is Jobs the most unique dude you’ve ever covered as a writer and journalist? Would you compare him to anybody?

WALTER ISAACSON: Steve is by far the most intense person I ever met, and he’s filled with contradictions. Who can I compare him to? Â NOBODY! He was more inspiring than anyone I ever met, and also the least filtered. “I’m a black-and-white kind of person,” he told me when urging me not to use a color picture of him on the cover of the book, and he even thought in black and white: You were a hero or a shithead. He could taste two similar avocados and proclaim one to be the best ever grown and the other to be inedible. Most of us have a filter, so that if our first reaction is that something sucks we pause or temper our words. Steve was brutally honest. That made him seem like an asshole at times. But it also ended up making him charismatic and someone who could create a loyal team.

RU. I’ve never seen Jobs’s acidhead hippie aspect foregrounded to this degree, particularly in the early part of the book.  It’s sort of a weird contradictory relationship to counterculture.  I have my own thoughts about this, but let’s start with yours.

WI: Steve represented the fusion of many strands. One was the hippie, counterculture, anti-authority, drugs, rock, rebel spirit of the late Sixties. Another was the hacker, wirehead, phone phreaker, geek hobbyist culture. You melded both of these when you launched Mondo 2000 in the 1980s. To these two cultural strands, Steve also added the entrepreneurial, startup, business mentality that was arising in the 1970s in Silicon Valley, especially after the advent of the microchip. He embodied a lot of contradictions. A seeker of Buddhist enlightenment who becomes a billionaire businessman. A misfit, acid-dropping, counterculture rebel who is a tough businessman. Someone with a new age and alternative spirit who also is a believer in technology and rational science. It all seems a bit weird, but it’s also kind of cool.

RU: Did you see any interest on his part in the political aspects of counterculture… aside from loving Joan Baez? Did he ever reference the antiwar movement or civil liberties struggles or environmental issues or even the war on drugs, to your knowledge?

WA:Â He didn’t seem all that interested in politics. His main interest was education reform. He really thought the school days should be longer; teachers should not have tenure, etc. He wanted to make ads for Obama in 2008, but wasn’t on the same wavelength as David Axelrod.

RU: One area where he contradicts most countercultural sensibilities was in his making Apple very much the opposite of open source and free software and all that. What intrigued me in the book was that he seems not to be motivated so much by greed as by artistic sensibility.  He saw himself as an artist and he was the director of these creations — almost like Hitchcock making a movie. It had to be just so.

WA: He really looked at himself as an artist. And he had the temperament of one. He was demanding, a perfectionist, and sometimes a control freak. He said he cared more about making beautiful products than about making a profit, and I believe him.

RU: For those of us who were around in the early days of digital culture, you could say Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in one breath… sort of like Lennon and McCartney. Â So was Wozniak a fluke? Â Did Jobs ever imply that he viewed it that way?

WA: Woz was not a fluke. Steve Jobs said he was 50 times better than any engineer he had ever met. He was particularly brilliant at a very specialized thing: designing circuit boards using the minimal number of chips. But the importance of that talent waned, and he did not care about the other aspects of Apple.

RU: Did he have a Sancho Panza… a partner outside of his family who sort of stuck by him?… or at least some career long accomplices about whom you could tell us a bit about their relationships?

WA: One of Steve Jobs’s longtime mentors was Mike Markkula, the first real investor in Apple. He became a mentor. He taught Jobs about focus and marketing and packaging. But he sided with John Sculley in the showdown of 1985, and when Steve returned in 1997 he asked Markkula to leave the Apple board.

RU: You were surprised that Steve asked you to write a biography and gave you free reign over it, given his love of privacy and control. Did he ever waiver? Any freak out moments when he tried to shut you down… or where you worried he might do that?

WI: The one thing I could never fully understand was why Steve Jobs did not insist on more control over the book. He kept saying he didn’t want to see it in advance. He said he knew I would write things that would make him mad, but he wanted me to be honest. He said he wanted to avoid any perception that it was an in-house book. He wanted it to feel independent. The only time he interfered was when he saw a proposed cover design and thought it was ugly. He asked for input into the cover. I agreed.

RU: What did you learn that surprised you most about his personal life as you researched the book?

WI: What most surprised me about his personal life was how it was connected to his professional life. He was intense and emotional in both. In both cases, he had a romantic new age side and a sensible, technological, rational, business side. These two sides ended up connecting in both his personal life and business life. In his personal life, the two strands connected in his marriage. It was both a romantic and rational marriage.

RU: I indicated at the beginning of this interview that Jobs was so unique that no budding entrepreneur could benefit from emulating him. But I wonder, what lessons are there in this bio for people who want to make world changing art or technology?

WI: The most important lesson is to have a passion for connecting art with technology. It was the lesson of the fusion of the hippie and tech geek of the early 1970s, as reflected in Mondo 2000, and it’s embodied in Steve’s life.

RU: Have you had any interesting responses to the book — for example, was anyone shocked or dismayed by the LSD references… or anything else?

WI:Â Some people responded to the book by focusing on, and being shocked by, his petulance. That misses the point. I tried to make the narrative a tale of how the petulant personality was connected to his passion for perfection — and how eventually he made that inspiring rather than off-putting.

RU: Do you think Apple can keep up the magic without Jobs?

WI:Â Apple has been infused with Steve’s belief in connecting art to technology. Tim Cook and Jony Ive get it. So do the other members of his top management team. They can make it work.