Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis: The Quantified Life Is Not Worth Living

""){ ?> By R.U. Sirius

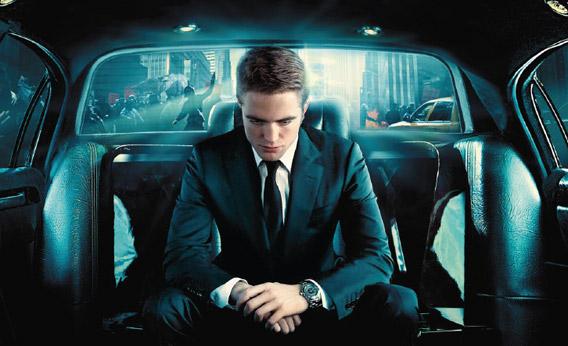

Eric Packer (played by Robert Pattison) — reigning master of the universe of unencumbered digital financial trading — spends most of his disastrous day in the back of a limo determined to make it across New York City in the midst of traffic chaos caused by a presidential motorcade, to get a haircut, but not, as we will discover, any haircut.

Impeccably dressed, physically perfect, emotionally smooth, and despite a series of sexual encounters during this single day with beautiful female subordinates — Packer’s world, until today, is nothing but data.

At the beginning of the film, we see massive data flows zipping around a small computer screen operated by a hacker employee, and we understand that his world of unfailing predictions based on this data has been disrupted by an error that threatens him with massive financial losses.  But Packer, despite the seeming practicality of the bad day he is facing, is more interested in his existential situation. He’s having a crisis of meaning and of feeling.

As he and his driver make their way through NYC’s jammed streets, various courtiers slip into his limo to talk about some aspect of his business situation only to be peppered by stark questions that tilt away from business and lean towards meaning. And yet, his quasi-philosophical inquiries  are all oriented towards calculation as opposed to insight (and how many of our singularitarian friends would acknowledge that a distinction exists).  Packer is in the vanguard of his generations’ and our culture’s reorientation from lived to statistical experience.

The film hinges on two particular events. Event one: Packer’s previously unfailing prediction machine has failed to predict a crisis in the yuan. Event two: Packer’s daily medical examination turns up a peculiar (and contextually funny) problem that I won’t spoil for you… but both problems revolve around the incursion of irregularity into his smooth world.

Here we have the Quantified Life at its apotheosis. Even in the midst of sexual encounters, there are conversations that seek information about the nature of the business and sexual relationships and — during the peak of one sex scene — his female partner reports on her successful jogging routine and provides a statistical particular about her fat-to-muscle ratio.

In mixed reviews, much has been made of Cronenberg taking on Wall Street capitalism (and let’s remember that all this is based on the critically underrated DeLillo 2003 novel of the same name) in a biting satire that’s not at all a comedy. There is that. But the critics miss the larger undercurrent, which should have clarified for them during the last scene (and I will spare you any further spoilers). Several shocking scenes (yes, this is Cronenberg), including the finale, bring home for us that Packer is seeking some experience — any experience — that is not quantifiable.  Whether he finds it or not, I’ll leave for you to sort out.

Oscar Wilde famously said of his countrymen, “They know the price of everything and the value of nothing.â€Â But he was thinking of craggy old industrialists who actually traded in things. For Packer, price and value are both de-prioritized by the ersatz bliss of those baptized in dataflow. It’s a cold but pleasurably high, until something unsmooth, like a poor person or a bodily peculiarity, makes an unpredicted intervention.